LONDON - What the crowd lacked in size, it made up for in noise. Fifty or so people waved Turkish flags and shouted their support for Recep Tayyip Erdogan, as he gave a speech at a think-tank in London.

Protesters responded with placards covered in a sinister image of the Turkish president and chants of "Erdogan, terrorist!"

The aim was to show that he "is not welcome in the UK", Elif Gun, a young activist, said.

"He is the killer of Kurds."

That is not a view shared by the British government. Erdogan's State visit on May 13 to 15 included a stiff Press conference with British Prime Minister Theresa May and a meeting with the queen.

The tour aimed to cultivate a blossoming relationship. In contrast to other Western powers, Britain was quick to offer the Turkish government its support after an attempted coup against it in 2016, and has remained quiet over human-rights violations.

It now hopes to benefit, with a number of arms deals in the offing.

Tony Blair's government toyed with the idea of an "ethical foreign policy", before giving in to economic imperatives. May has shown little regard for such concerns.

Since the vote in 2016 to leave the European Union, the government has published a slew of policy papers promising renewed engagement with the wider world, under a "Global Britain" slogan.

In practice, this has proved difficult. In the past year, Britain has lost an embarrassing vote at the United Nations (over the Chagos islands) and failed to send a judge to the International Court of Justice for the first time in the court's history.

Ironically, its greatest success has been in the EU, where May convinced 18 countries to expel Russian diplomats after the poisoning of an ex-spy in Britain.

Much attention is, thus, focused on strengthening bilateral relations. Doing so has often required ministers to bite their tongues.

In Africa, Britain has scrambled to improve relationships with some of the continent's worst human-rights offenders.

Sudan's President Omar-al Bashir has been indicted for genocide by the International Criminal Court (ICC), but Britain now has a "strategic dialogue" with the country, and in December, hosted a Sudan trade forum in London.

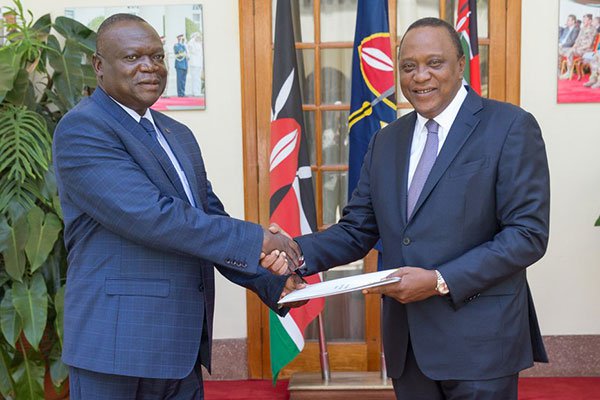

It is leading a charge to embrace the new President of Zimbabwe, Emmerson "the crocodile" Mnangagwa, who many believe will prove little better than his predecessor, Robert Mugabe.

Britain is promoting debt write-offs for Zimbabwe in exchange for commitment to reform.

Last year, Liam Fox, the trade secretary, buttered up another president, who has attracted the attention of the ICC, Rodrigo Duterte of the Philippines, who is being investigated for crimes against humanity committed during his war on drugs.

Drumming up trade, Fox wrote in a Philippine newspaper that Britain had a strong relationship with the country, built on "shared values and shared interests."

As well as visiting South-East Asia, diplomats are spending lots of time in the Gulf.

Foreign governments are well aware of Britain's new predicament. As Mnangagwa told the Financial Times: "Brex, how do you call it? Brexit. Yes, it's a good thing because they will need us. What they've lost with Brexit, they can come and recover from Zimbabwe."

This is uncomfortable for some cabinet Brexiteers. During the referendum campaign, Michael Gove, a leading Leaver, accused the EU of "appeasement" regarding Turkey, where, he argued, "democratic development has been put into reverse".

Around the same time, Boris Johnson described Erdogan as a "wankerer" — to rhyme with Ankara — and suggested that he had had sex with a goat, in an entry for a poetry competition (he won £1 000).

Alas, Johnson, now Foreign Secretary, was on an urgent overseas mission this week, and unable to meet the president.

- Economist

Concern over Masvingo black market

Concern over Masvingo black market  Kenya declares three days of mourning for Mugabe

Kenya declares three days of mourning for Mugabe  UK's Boris Johnson quits over Brexit stretegy

UK's Boris Johnson quits over Brexit stretegy  SecZim licences VFEX

SecZim licences VFEX  Zimbabwe abandons debt relief initiative

Zimbabwe abandons debt relief initiative  European Investment Bank warms up to Zimbabwe

European Investment Bank warms up to Zimbabwe  Young Investment Professional (YIP) Graduate Programme 2019

Young Investment Professional (YIP) Graduate Programme 2019

Young Investment Professional (YIP) Graduate Programme 2019

Young Investment Professional (YIP) Graduate Programme 2019

Editor's Pick